Pilgrimage to Oaxaca

Our Travel Columnist gave us a gorgeous excerpt from her book, and now we're all in on this magical place for our next vacay!

MY PILGRIMAGE TO AN ANCIENT city began haphazardly. Russel and I were headed back to where art meets commerce—New York City, via the Panama Canal. After crossing the Sea of Cortez, we spent Thanksgiving in Puerto Vallarta and Christmas in Zihuatanejo. Then we sailed south along the mainland, ghosting along day and night with only our big, colorful drifter up in the light but steady offshore breeze. The famed Gold Coast was beautiful in a wholly different tropical way, but each harbor was busier than the last, their high- rise hotels and crowded beaches seeming a world away from Baja. South of Acapulco we sailed into Puerto Angel, a quiet fishing village whose bay was roomy and calm, with quite a few cruising boats in it.

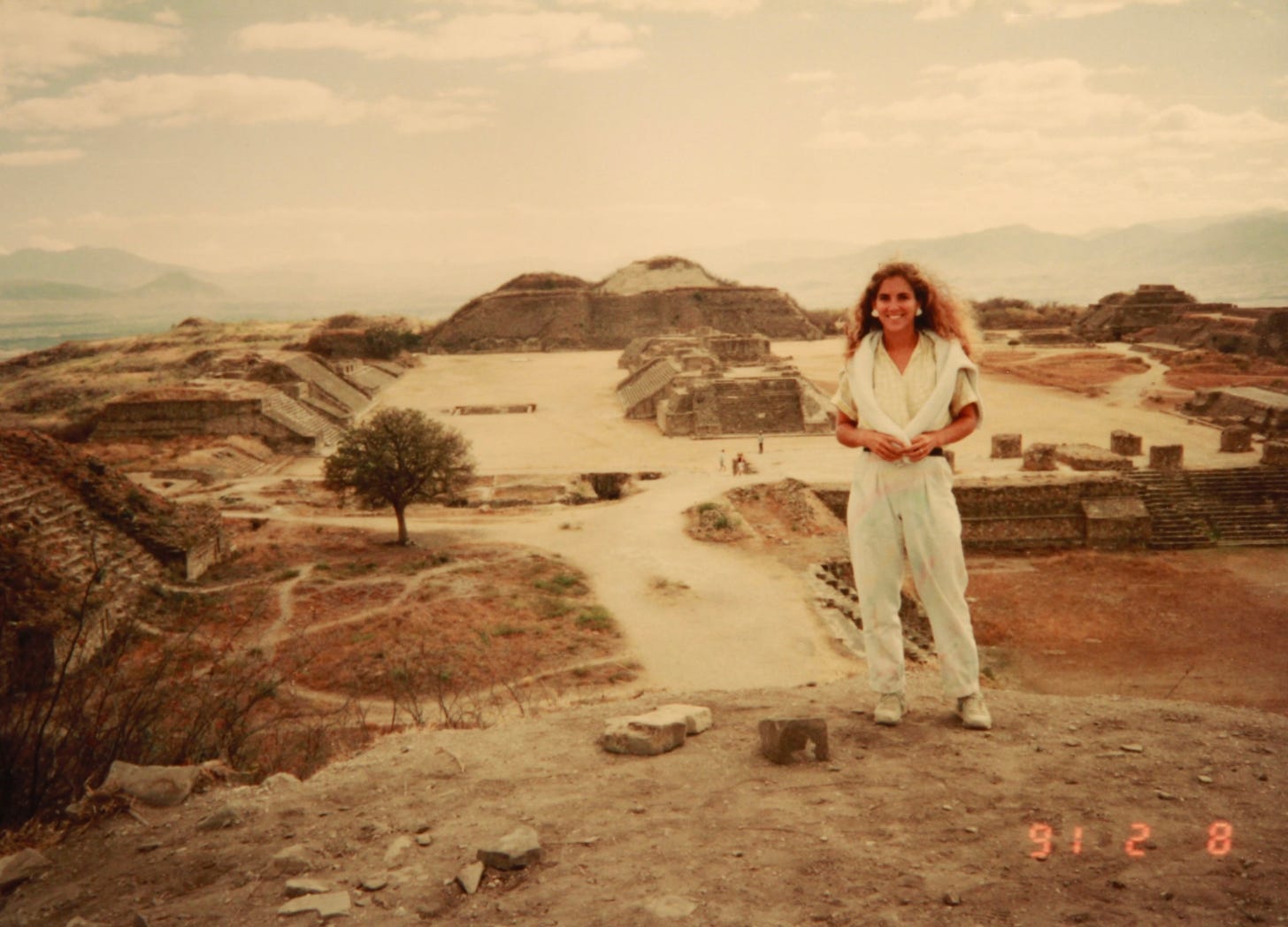

Consulting our map, we saw one of the grand old colonial cities of Mexico was quite close by. Just beyond the coastal mountains lay Oaxaca, famed for its beauty and for the nearby ruins of Monte Alban. Some new friends in the anchorage offered to keep Charlie for us so that we could journey there by bus. We hadn’t seen any of Mexico’s pre-Columbian treasures, so we planned to end our inland trip with a day at the ruins.

A week later, we watched the stately buildings and tree-lined boulevards of Oaxaca slowly give way to fields and hills. For two days we’d strolled the streets, listened to music in the plaza, and browsed through the shops. Now it was time to see the ruins of Monte Alban.

The ride took two hours because of a traffic jam at the edge of town. Our stalled bus sat there, gridlocked, its windows wide open to the warm air, diesel smoke, and blaring horns, its seats filled with impatient travelers from all over the world, carping in their native tongues about the delay. Beside us was another bus, returning from the morning market with crates, bushels, and livestock strapped, tied, and balanced upon it. A goat stood upon the roof, bleating piteously as the slow minutes ticked past, and I began to wonder if we’d made a mistake.

Finally, the cars all began to move, and soon we were speeding up a winding road as the driver tried to make up for lost time. At the top of the mountain, we descended slightly into a verdant plateau, and the bus rumbled over to a dirt parking lot at the base of a grassy hill.

The driver directed us up to the site’s information center, where a guide gave us maps and told us not to buy anything from the vendors who would approach us in the ruins, hidden from sight beyond yet another steeply sloping hillside. Glad to be out of the bus, Russel and I quickly headed up the hill and were somewhat winded by the time we reached the summit.

We were standing atop the outer walls of a stone city; we’d been climbing the sides of its fortifications. Tall stone walls marched away before us, encompassing a vast expanse of grass, crisscrossed by walls and walkways and dotted with the shells of ancient buildings.

The walls joined again, many hundreds of yards distant, at the base of an immense pyramid as high as the one upon whose base we now stood. It was cooler up here, and a breeze lifted the hair off my sweaty brow. Far away were blue-gray mountains, some with icings of snow on their peaks, ringing the high green valley that surrounded us. Beyond the mountain ranges were white banks of cloud, which seemed held in place there, for above us the sky was as blue as some celestial sea.

Without speaking, Russel and I clasped hands and walked through a narrow stone gate toward the center of the pyramid, then turned and began to climb the steep stairs. Each of the steps had a slight dip at its center, where generations of holy men, soldiers, prisoners, and slaves had placed their sandaled, booted, or bare feet while ascending the awesome giant.

Silently, we stepped up and up, our shoes making no sound on the stone, the voices of people behind us falling away as we climbed higher. Even with the altitude and the steepness of the stairs, my breath came easily, but my head and chest seemed to lighten with each step until, at the top, I was almost faint. Turning to survey the scene spread before us, I sank down upon a slab of rock whose surface had seen offerings long before written history.

Below us, the two dozen other visitors had dispersed into the immensity of the grounds, their tiny forms nearly lost among the low walls and tall grasses. One family was climbing the staircase toward us, and when they had nearly reached the top, we gave up our spot and headed back down. When Russel and I passed the others, we noticed that their conversations were hushed and reverential. In fact, there was little sound at all as people climbed and wandered about, and none of the calling and shouting that often accompanies large groups out of doors. Even the children seemed overwhelmed and stood quietly staring, clearly struck by the site’s awesome scale.

We walked wide pathways of gray rock between high walls and above ledges, pausing to examine the intricate carvings and cunningly laid stonework at every turn. Plazas and boulevards, courtyards and playing fields were ruined or overgrown, but even ringed as they were with tumbledown stone fences, the grand design was abundantly clear. It had been a city of open markets and meeting halls, but one where private spaces could be found for quiet contemplation or conversation. It was eerie to stand alone in the middle of a huge central mall that once teemed with vendors and shoppers, its stalls full of colorful fruits and vegetables. Sitting on the raked stone bleachers that overlooked the ball court, I could easily imagine its stands filled with spectators joyously cheering on their favorite athletes.

During the bus ride, I’d read a pamphlet that conveyed the little that was known about Monte Alban. It was inhabited by the Olmecs, Zapotecs, and Mixtecs, though perhaps other peoples that modern scientists have not yet named had lived here as well, earlier than those we can prove or between those generations we know of. No one was sure of how the incredible structures were built, by whom, and, chiefly, when and why the original inhabitants left. Also unknown was the meaning of some of the bas-relief carvings of people on the inner walls; they look like dancers but are believed to be diagrams of physical ailments or maladies for future physicians’ reference.

All these facts circled inside my head like the eagles that flew high in the vault of blue above me. None of it meant anything as I gazed unseeingly at the sky, feeling my pulse race with more than exertion. This place had all the mystery of Stonehenge and Easter Island, but there was more here than that. This had been a city, and it still felt populated. Not with history, but with life. Living people, families, had lived in these rooms, walked these paths, watched games played on these ball courts.

And they worshipped here, certainly, as well. Brought wine, corn, or cattle, and yes, undoubtedly, human beings—the chosen ones whose blood would spill for the pleasure of the gods. We can’t begin to understand why they believed as they did, but that this was a temple to the gods those people chose to worship, there seems little question.

I have been to many churches and cathedrals in my life, some modern, some hundreds of years old. Only a few of them have the simple, wondrous quality of a holy space: a peaceful, serene quiet, and a sense, even when the buildings themselves are empty, of fullness. I’ve always believed that feeling comes from the quality of the time spent there, in individual and group prayer, at weddings, christenings, and funerals, over years. Many years of love and belief, of faith, can permeate a physical place, whether it be an illustrated mountain cave or a soaring Gothic cathedral, and persist long after its inhabitants are gone. This ancient vessel of a city, hewn by hand from native stone high in the mountains of Mexico, had been full for centuries and felt holy.

I saw no visions at Monte Alban; no heavenly voices spoke to me; and I didn’t feel the need to pray or leave offerings. There was no primal urge to research and delineate my family’s complex genealogy, though the blood of some of the city’s former inhabitants may run through my veins, passed down from Nena to my mom.

But something did happen to me there, an epiphany both unexpected and ephemeral. Standing on those centuries-old stones with the wind of that timeless valley in my hair, I saw that humans had created all of this, not just to be a part of something great but to aspire to something greater. They carved beautiful designs into solid rock and built their majestic temple as far into the sky as they could, and then they worked, played, worshiped, and danced in the shadow of it. It was stunningly clear to me at that moment, because the stones they laid are still there to prove it.

Not long after that inland trip, Russel and I motored Watchfire into the first of the massive locks that make up the Panama Canal. That first locking-through was so full of things to attend to that the physicality of the Canal didn’t sink in, past whoa, this is big. After the second lock, we began to relax, confident in the handling of our boat by the adept (and mandatory) hired captain and line-handlers. Moving into the last of the Pacific-side locks, I was finally able to look around and appreciate the labor that had gone into this modern wonder of the world.

High atop sheer cliffs of cement that lined the sides of the lock, small figures made us fast to the massive cleats. Charlie followed my line of sight, spotted the people, and barked. I laughed, and she relaxed, tongue lolling, happy to have warned off the intruders. The water level quickly rose in the immense square vat until it was full, half salt and half fresh. Then came the grinding of the monstrous gears as the immense doors slowly parted to reveal a waterway, a channel cut by human hands through the lush jungle and earth of a continent to join two oceans.

As we moved out into the canal, between the cliffs of red clay, I was again struck by the ability of humans to conceive of an incredible goal and make it a reality. Perhaps that is why people journey to pyramids, aqueducts, cathedrals, and bridges, to catacombs deep below the ground, great temples in the middle of vast deserts, and statues or shrines carved from solid rock atop towering peaks. Seeing and even touching the wood, steel, or granite engenders a response that resounds within us. If this tremendous undertaking could be realized, what task cannot? If faith could build this monument, belief this city, determination that bridge, there is nothing, then, that humans cannot achieve.

That being so, we two could surely fashion our own unique relation-ship aboard this boat, and continue to create our art, and our life, together.

I grinned over at my husband, holding the tiller lightly as Watchfire was pulled along through the waterway, still safely bound to the boats beside us. Russel caught my eye and beamed. The voyage was far from over, but we shared a thrilling moment of completion, of achievement, of joy.

You can buy Jenny's memoir, from which this piece is excerpted, right here.

You can also find Jennifer on Facebook, Instagram, TikTok and Twitter.